Return to Study Guide: How to Study the Bible, by Jeffrey Bruce and Brian D. Asbill

Download PDF (5 pages)

Module 6: OT Genre Studies 1: Narrative and Law

I. Now that we understand the nature and significance of genres, we can begin to look at specific biblical genres so as to better understand the rules by which they operate. Preliminary remarks will be made on each genre, followed by specific hermeneutical rules relating to it. This week, we will tackle the predominantly Old Testament genres of Narrative and Law.

II. Narrative

A. Preliminary Remarks:

1. Definition

a. A General Definition – “An account of particular events and characters having a beginning and an end.”

b. A Biblical Definition – Stories designed to show God at work in creation and among his people.

c. From this we see that narratives are what we generally consider stories. However, these are not just any stories, but have a decidedly theological flavor.

2. This is the most common genre in the Bible, comprising roughly 40% of the Old Testament (See Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Joshua, etc.).

3. In regards to the importance of historical background, it is less important for the study of this genre.

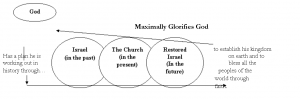

4. It is good to understand the importance of worldview in relation to this genre. As Westerners, we tend to think in existential, narcissistic, and ahistorical categories. When reading narrative, we need to replace this worldview with one that looks more like the following: SEE GRAPH

B. Specific Rules:

1. Three levels of Narrative:

a. The Top Level – Redemptive History. This level of reading relates to the universal plan of God, dealing with issues such as the fall, sin, and redemption.

b. The Middle Level – Israel. This level addresses issues such as the call of Abraham, the deliverance from Egypt, the Davidic line, the exile, etc.

c. The Bottom Level – The Individual. Here are found all the hundreds of individual stories that make up the other two levels.

2. From the following, we see that the ultimate point of OT narrative is to illustrate that God is the protagonist, and even the hero. It is the divine drama that is unfolding, and it is this top level of reading that takes precedence. The question to ask in this genre is thus, “What does this passage tell us about God (the Hero), His plan, and the role that His people should be playing in His plan?” Of secondary importance is this question; “What positive or negative model might this passage be setting before us to teach us about trusting God in the midst of His plan?” The divine element takes primacy, while human examples are secondary.

3. There are a variety of “subgenres” to be aware of when reading narrative. For example:

a. Report – A brief, self-contained narration, usually in third-person style, about a single event or narration in the past.

b. Heroic Narrative – A series of episodes that focus on the life and exploits of a hero whom later people consider significant enough to remember.

c. Comedy – A narrative whose plot has a happy ending, in some cases through dramatic reversal (see Genesis 37-50).

4. Because narrative is story, it is important to read it in big chunks to get the larger picture of what God is doing in redemptive history.

5. One must be wary of reading prescription into passage. While narratives are theological history (i.e. history that is trying to teach us something about God and our relation to him), one must not assume that every story is teaching explicitly some virtue. Often they only record what happened.

|

Case Example #7: Genesis 37-50 Often when reading Biblical narrative, we focus on the supporting cast rather than the protagonist (i.e. God). This is particularly true in regards to the story of Joseph. Many tend to focus on him and his character when preaching through this portion of scripture. However, this is not the point. As Fee and Stuart say, “Joseph’s lifestyle, personal qualities, or actions, do not tell us anything from which general moral principles may be derived. If you think you have found any, you are finding what you want to find in the text; you are not interpreting the text.”[1] Instead of focusing on Joseph, our focus should be on God and his preservation of the promised seed of Abraham through his provision of Joseph. We can see how reading from the “top level” helps in reorienting how we look at scripture, and how we prioritize in interpretation. [1] Ibid., How to Read the Bible, 86. |

II. Law

A. Preliminary Remarks

1. Definition

a. Covenant stipulations which Israel was expected to keep under the Mosaic Covenant.

b. “the covenant or relational agreement that God made with Israel at Mount Sinai after He delivered her from four hundred years of bondage in Egypt.”

2. The concept of law was not unique to Israel as other Ancient Near Eastern codes of law existed (e.g. The Code of Hummurabi).

3. It spans (roughly) from Exodus 20 to Deuteronomy 33.

4. In terms of historical background, it is relatively important (more so than with narrative) but still not incredibly important.

5. Law must be understood in the context of the covenant. If one fails to do this, the law is reduced to a set of legalistic rules. God’s covenant with Abraham and his deliverance of Israel from Egypt demonstrate that the law is lived out in gratitude to God. It is highly relational.

6. The Law itself is a form of covenant. Specifically, a Suzerain covenant, which is typically made between a king and his vassals.

Stein lists the typical items in this covenant:

a. Preamble

b. Historical Prologue

c. Stipulations

d. Provision for Continual Reading

e. List of Witnesses

f. Cursings and Blessings

g. Oath

B. Specific Rules

1. There are numerous forms of Law that must be acknowledged when interpreting.

a. Casuistic Law – Law that treats primarily civil and criminal cases, generally with a distinctive “if…then” style.

b. Apodictic Law – Laws promulgated in unconditional, categorical directives such as commands and prohibitions.

c. Legal Series – A number of laws phrased in a similar style.

d. Legal Instruction – Law the instructs priests in professional matters such as ritual procedures.

2. Interpreting the OT Law as a New Covenant Believer:

a. Fundamental Principle – “All of the OT applies to Christians, but none of it applies apart from fulfillment in Christ.”

b. Ceremonial Law is fulfilled in Christ, and thus doesn’t need to be obeyed.

c. The ethical laws of the OT are still operative for the New Covenant believer.

d. In general, look for the underlying principle behind specific Old Testament laws (cf. 1 Cor 9:8-12).

e. Laws that don’t apply specifically still teach timeless truths.

|

Case Example #8: Leviticus 19:27 Many Christians have used this passage as decisive evidence that getting tattoos is evil. I’m not going to say whether I agree with this one way or the other. Instead, I want you to consider the passage in question. Here are some questions: · What type of law is this? · What is the surrounding context in which it is presented? · How is this law fulfilled in Christ? |

Return to Study Guide: How to Study the Bible, by Jeffrey Bruce and Brian D. Asbill